3. Tasmanian Midlands -Threatened Marsupials of Tasmania

Tasmania is Australia’s last refuge for some of our most endangered animals. The marsupials, the Eastern Bettong, the spotted tailed quoll , the eastern barred bandicoot and the Tasmanian devils are now classified as endangered. The threatened mammals are key stone species that have an important effect on the food web of the ecosystem. They are part of an interdependent ecosystem including bushland birds and native insects that make up the biodiversity of the landscape. Biodiversity describes the variety of species of plants, animals and microorganisms, their genes, and the ecosystems they are part of. It is about the complexity of life in an area. If any single species in that area disappears, it affects all the other species in that same area.

We can all help to maintain and protect this rich biodiversity of the Midlands. A good way to help is to learn about the plants and animals that make it so special.

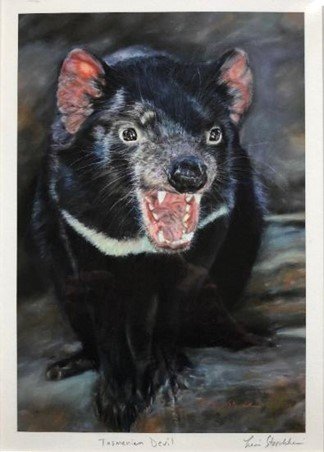

Tasmanian Devil - Sarcophilus harrisii

The Tasmanian devil got its name from Europeans who heard the mysterious screams, coughs and growls from the bush. The dog-like animal with red ears, wide jaws and big sharp teeth was named "The Devil". Aboriginal people also have several names for them, one of which is “purinina”. It is the world’s largest surviving carnivorous marsupial. The Tasmanian tiger once held this title but it is now extinct.

The Tasmanian devil makes fierce noises, from harsh coughs and snarls to high pitched screeches. When threatened or even around feeding time with other devils it will bare its teeth and growl. This is a challenge to other devils, and happens before a fight. Many of these spectacular behaviours are bluff and part of a ritual to reduce harmful fighting when feeding together at a large carcass.

Devils were once found on mainland Australia. But it is believed the devil became extinct on the mainland some 3,000 years ago probably due to increasing aridity and the spread of the dingo. Today the devil is a Tasmanian icon but this hasn't always been the case. Tasmanian devils were considered a nuisance by the Europeans of Hobart Town, who complained of raids on their chickens. In 1830 the Van Diemen's Land Co. introduced a bounty to remove devils, as well as Tasmanian tigers and wild dogs, from their northwest properties.

For more than a century, devils were trapped and poisoned. They became very rare, seemingly headed for extinction. But the population gradually increased after they were protected by law in June 1941. During 1996 it became evident that Tasmanian devils were again under threat – this time from the Devil Facial Tumour Disease, which killed more than half of the surviving population.

The devil has a thick-set, squat build, with a big broad head and a short, thick tail. The fur is mostly or wholly black, but white markings often occur on the rump and chest. Devils can be found in Tasmania from the coast to the mountains.

The Tasmanian devil is mainly a scavenger feeding on whatever dead animals they find. Their very powerful jaws and teeth allow them to completely devour their prey - bones, fur and all. They waste nothing! They can also be predators, eating small birds, snakes, fish and insects. The scat of a Tasmanian Devil has tell-tale fur and bones. (picture??)

The Tasmanian devil is nocturnal. During the day it hides in a den- in hollow logs, caves or dense bush. It can travel great distances - up to 16 km - along trails in search of food. Devils usually amble slowly with a characteristic gait but can gallop with both hind feet together. Young Tasmanian devils are quite agile and can climb trees. Although not territorial, Tasmanian devils have a home range, which can be very large if resources are scarce.

Tasmanian devils can swim and seem to enjoy water and will wade and splash about, even sitting or lying down in it to stay cool.

The biggest threat came to the devils in the mid 1990 ‘s with the Devil Facial Tumour disease. Devils spread the disease through fighting and mating. They get lumpy tumours around their heads and necks so that they can’t eat and can die of starvation within six months of symptoms showing. Tens of thousands of Tasmanian Devils have died from DFTD, and it’s this ongoing outbreak that has caused the Tasmanian Devil to be classified as Endangered under Australian and Tasmanian legislation.

Eastern Bettong - Bettongia gaimardi cuniculus

The bettong is a small wallaby that has unique hind limbs, perfect for hopping, and short forelimbs used for foraging. They are coloured brown-grey on top and have white or light bellies. The tail of the bettong is long and is equal in size to the head and body. It uses its tail for balance and can also grip and move smaller objects. Adult Bettongs are usually 30cm and can weigh up to 2kg.

Bettongs are omnivores and love eating seeds, roots, bulbs and insects but their favourite meal is an underground fungi known as truffles. They use their forelimbs to dig up this meal, which makes up a large part of their diet when available. Animals like bettongs that eat fungi are important to the health of the forest as they spread fungi spores.

Bettongs were once common along the coastal areas of eastern Australia, from south-east Queensland to the south-east tip of South Australia. Due to the introduction of the fox and the European rabbit, this species of bettong is no longer found on mainland Australia and is considered threatened in Tasmania. Bettongs like dry, open eucalypt forests and grassy woodlands so they prefer eastern Tasmania. They are nocturnal, spending daylight hours camouflaged in a nest of grass.

While common in pockets of Tasmania, bettongs are wholly protected as their habitat is threatened by land clearing. Repeated use of 1080 poison for wallaby control on private land and the constant threat of feral cats continue to affect their safety.

At night bettongs emerge to feed. Several species selectively feed on truffles – the underground fruiting bodies of mushrooms – but most also eat a wide range of foods: roots, tubers, leaves, invertebrates, grubs, fruits and seeds. Bettongs, like bandicoots, are important ecological engineers. Their digging plays an important role in decomposition of leaf litter (thereby reducing fuel loads and fire risk in dry grassy forests and woodlands) and in dispersing fungal spores and plant seeds.

Eastern Barred Bandicoot - Perameles gunnii gunnii

The cute little eastern barred bandicoot is a small marsupial with a slender, elongated head and big ears. Its fur is greyish brown, except for its hindquarters which have the three dark stripes that give the animal its name. These differ from the brown bandicoot, which does not have stripes. The belly, feet and short, thin tail are white.

Eastern barred bandicoots spend most of their day in a shallow hollow in the ground with a dome of grass pulled over the top, like the bettong. Only one adult bandicoot occupies a nest, although young may share the nest with their mother for a week after they first leave the pouch. After dusk, they emerge and immediately begin foraging for food. Bandicoots are solitary animals and only mix with others when they breed.

In Tasmania, young are born between late May and December. During a single breeding season a female may produce 3-4 litters with a litter size of 1-4 young. A female bandicoot can give birth to as many as 16 young in one year! However not many young survive because of predators and disease. The life-span of the eastern barred bandicoot is less than 3 years.

Bandicoots are omnivores but their favourite food is insects, using their small claws to dig for worms, grubs, crickets and beetles. They poke their long nose into the ground to sniff out these creatures. Evidence of Eastern barred bandicoots can be found by finding cone shaped holes in the ground and little pellets like cylinders with insects and seeds embedded in them.

Researchers put out over 180 wildlife cameras and not one eastern barred bandicoot was photographed in the Midlands.

Spotted Tailed Quoll - Dasyurus Maculates

The spotted-tailed quoll is the second largest of the world's surviving carnivorous marsupials. They can be reddish brown to dark chocolate brown with white spots on the body and tail (unlike eastern quolls which do not have spots on the tail). The species is much larger than the eastern quoll, measuring up to 130 cm long and 4kg in weight. The eyes and ears of the spotted-tailed quoll are comparatively smaller than those of fellow marsupial, the eastern quoll. The spotted-tailed quoll looks strong with a thick snout and wide gape.

The spotted-tailed quoll also lives on the east coast of mainland Australia, but is very rare and is threatened there. They are most common in cool temperate rainforest, wet sclerophyll forest and coastal scrub along the north and west coasts of Tasmania.

Spotted tailed quolls are tree climbers and live in dens. They often make dens in tree hollows, rock cavities, fallen logs or underground burrows. They are usually solitary and nocturnal (they hunt at night), although sometimes forage during daylight.

Quolls eat a wide variety of foods- as long as it is meat. They eat animals- dead or alive. They are good hunters that kill their prey by biting on or behind the head. They range a few kilometers hunting rats, gliding possums, small or injured wallabies, reptiles and insects and sometimes birds and eggs.

By clearing native vegetation in the Midlands the quolls have lost their habitat ,sources of food and limited the number of hollow logs suitable for dens.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the original owners, the Palawa people and the use and crossing of the Midlands where we meet with our partners to share, learn and raise awareness about the land:

Paredarerme nation people, Laremairremener and Poredareme tribes, Luggermairrerpairrer tribe and the Tyrrernotepanner tribe