2. Tasmanian Midlands - The Background Story

For over 60,000 years multiple Aboriginal nations lived with the marsupials of Tasmania. The Palawa people managed and farmed the land, burning and creating grasslands and open woodlands for hunting. Flint stones for cutting and scraping were quarried and traded from a quarry site near Ross. The Aboriginal custodians, the Tyerrer-note-panner people, speared and trapped emu with nooses and the women collected Tasmanian emu eggs and the big freshwater mussels from the rivers. The Midlands was a meeting place for Palawa tribes travelling from the east coast to the western highlands and between north and south exchanging tools, shells and red ochre and hunting wildlife. The country was full of wallabies and kangaroos, possums and echidnas, as well as ducks and swans in the wetlands. Wombats dug deep burrows and flocks of emu ranged the grasslands and woodlands.

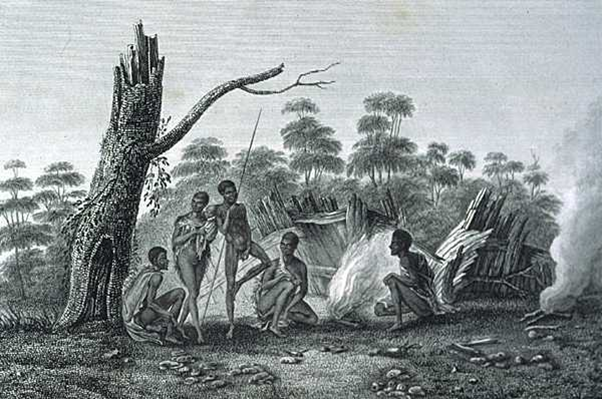

French depiction of Aboriginal life, 1807 (Tasmaniana Library, SLT)

The river banks and wetlands grew reeds and grasses that were spun and woven for making bags and string. Trees were used to make shelters and long hunting spears.

The Palawa people lived happily with the marsupial carnivores such as Tasmanian Tigers (the thylacine), Tasmanian Devils, and Spotted tailed Quolls for over 35,000 years. The Eastern Bettong hunted for truffle fungi and carried grasses with their tails. The Eastern Barred Bandicoot made conical holes in the soil looking for grubs and hiding from the wedge tailed eagles. Emus featured in stories and songs, and there were lots of different names for them, including gonanner, ponanner and tooteyer. Emu feathers were used to decorate inside Aboriginal huts, and used for insulation. (Greg Lehman).

In 1803 a big ship came into Risdon Cove. On board were 49 convicts, sailors and settlers. They brought with them rabbits, blackberries and sheep. The first European settlement was established in Hobart Town. Gradually, as the population of the Island increased, the way north was established. The military forces, and settlers looking for land, passed up and down through the Midlands until distinct tracks were formed. By Governor Macquarie’s orders in 1812, a military guard near Ross and Campbell Town protected travellers and pioneers from attacks by bushrangers and indigenous people who were being dispossessed from their land.

The English colonised this area of open grasslands that they found were perfect for raising sheep and cattle. From 1825 land grants divided the landscape into portions of 100 square miles. The good grazing land was fenced in straight lines. They cleared large areas. In the 1820’s merino sheep were brought from England.

“About three miles north from Ross Bridge is the government farming and grazing establishment. They have reserved to themselves twenty thousand acres and the ‘best grazing land in the Island moderately wooded and well watered”.

In 1823, some 441,871 acres of the best Aboriginal hunting grounds were granted to settlers. They built permanent homes, planted crops and gardens and imported valuable stock. The Palawa people lost their tribal lands to fenced paddocks for sheep grazing and could no longer manage their land with fire.

In 1822 the main road from Launceston to Hobart was built. A party of at least 30 labourers started from each town simultaneously.

The Aboriginal people were not happy about losing their hunting grounds and no longer managing the land using fire. The British farmers hunted their wallaby, kangaroo and emu with guns and dogs. Wallaby and emu were a major food source for the Europeans.

Until 1824 the Aboriginal groups with elderly and young continued to follow established paths and visit traditional gathering spots. (Boyce 2101 p 197). From 1824 at the start of the Black War, Aborigines were massacred by groups of armed bushmen. Governor Arthur declared martial law in 1828 and tried to round up the tribes. George Augustus Robertson led a ‘Friendly Mission’ aided by cooperative Aborigines, Truganini and Woorady.

A reward was offered for the capture of Aborigines, £5 pound for every adult and £2 for every child taken alive. All Tasmanian Aborigines were removed from the Tasmanian mainland to the Furneaux Islands including Flinders and Cape Barren. The number of Palawa people went from an estimated 7,000 at the time of the arrival of Europeans to fewer than 250 by 1830. ( J Boyce, Van Diemen's Land, 2010 Melbourne Black Inc.) The Black War ended in 1842.

In 1824 a big ship the Ardent owned by Roderic O’Connor had arrived from Ireland. He brought with him free settlers, as well as furniture and silverware treasures. He established Connorville at Cressy. The open landscape was perfect for sheep grazing on native pastures.

There were estimated to be 280,000 sheep in Tasmania by 1840 and 24,000 non-Aboriginal people.

Photo:National Library of Australia

Chiswick House in Ross was established in 1841 with a 2000 acre grazing land grant to a Hamburg shipowner and merchant, Benjamin Horne who arrived in Tasmania in 1823.

The new farmers were keen to bring other useful plants and animals from their homeland. In the 1830’s fallow deer, rabbits and hares were introduced to the Midlands. Farmers planted gorse as fencing on their properties that also provided a good place for the rabbits to hide. They brought in trout and perch, hawthorn and thistle. Sheep over-grazed the native grasses. Farmers planted introduced grasses that were a richer food source for the sheep than native grasses but these needed to be irrigated and fed with chemicals. Soil was compacted and erosion increased. Jane Williams looked back at her arrival in 1822 and noted since the large herds were introduced the flowers had become comparatively rare, she also found that in some of the ‘fine sheep country’ all the trees were dead but the wattles.

The early colonials loved hunting emus and kangaroos. “The Palawa people could no longer burn the land and that probably affected what habitat was available for emus to travel through and the food that they ate,” Mr Derham said. By 1865 the last Tasmanian emu was hunted.

At that time there was an estimated 5000 thylacine. The world’s largest marsupial carnivore was known as the Tasmanian Tiger, because of the stripes on its back. In 1888 the Tasmanian Government set a bounty for the Tasmanian Tiger of £1 per full-grown animal and 10 shillings per juvenile animal destroyed because the thylacine were stealing sheep. The program went on until 1909 with more than 2180 bounties paid out.

In 1890 the Launceston Examiner reported that: “a well known trapper at Connorville, brought to the Longford Police station three mauve tiger heads for which the government allowed one pound each. These animals are rarely met with, only a few being now and again captured in the back blocks”. At least 3500 thylacines were killed through human hunting between 1830 and the 1920s.

Hunter poses with dead thylacine, 1869. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Habitat, including the shelter and food for the native mammals, not just for the thylacine, was lost.

In the 1950’s wool production intensified with the use of superphosphates. This fertiliser washed into the rivers. The clearing of the native woodlands in the Midlands for more intensive farming led to further lack of shade and shelter for the marsupials- the devils, the bettongs, the eastern barred bandicoots and the spotted tailed quolls.

Tasmanian soils contain salt. Trees absorb water and take the salt and water deep into the ground. When the trees are cleared the shallow-rooted grasses that replace them don't absorb as much water so that the ground-water rises to the surface making it difficult for plants to grow.

At the same time overgrazing eroded the soil that then washed into the rivers. Willows were planted on the riverbanks to reduce the erosion but they took over the banks and choked the rivers. Gorse that was introduced for fencing, became an invasive weed, smothering large areas of the hilly and stony ground. It also took over the understorey of native vegetation.

Rabbits and hares competed with native mammals for food and shelter, and further eroded the land.

In 1996 a dead eucalyptus tree became a landmark on the side of the road north of Oatlands. It was painted red by artists for Landcare to symbolise Tasmania’s tree decline and the widespread erosion in the Midlands. A few months later it was burned down by vandals. In 1997 four giant letters spelling T R E E and a small plantation of trees replaced the red tree.

More recently irrigation pivots were introduced throughout the Midlands for intensive cropping. The long arms that swept through the paddocks had to be clear of vegetation so trees and native plants were cleared for their path.

From 2017 Tasmanian farmers were able to clear up to 40 hectares of native forest per year as the government relaxed land clearing rules.

The marsupials found they had nowhere to hide. The Midlands was one of the first areas of Australia cleared for agriculture. 93% of the Midlands was private farmland and less than 2% of the native plants and animals were protected in small, scattered patches. In these small patches there are rich treasures worth protecting such as the Black-tipped spider orchid Caladenia anthricina (critically endangered), the Pungent Orchid (Prasophyllum olidum) and Golfers leek-orchids (Prasophyllum incorrectum).

After 200 years of farming only 3% of native grasslands and 10% of native forest were left. The distinctive dry native vegetation ecosystems had become just small mosaics amongst paddocks of sheep and pivot irrigation. Most remnant patches were degraded through loss of understorey plants, tree decline and invasion by weeds and pests, and were drying out through climate change. This means that many native animals lost their habitat with real risks of further species extinctions.

The Midlands was declared by the Australian Government as a Biodiversity hotspot with many endemic species found only in Tasmania. It is the only Biodiversity hotspot in Tasmania and one of 15 areas in Australia and over 37 worldwide. A hotspot is identified when an area of high biodiversity has lost more than 75% of its primary vegetation. Areas with many threatened endemic species were identified as hotspots. Hotspots are alarm calls to prevent long-term and irreversible losses.

Vegetation loss including threatened native orchids, soil erosion, dryland salinity and invasion by introduced pests like feral cats and deer and weeds such as willows and gorse, are seriously threatening our precious marsupials, the Tasmanian devils, the spotted tailed quolls, the eastern-barred bandicoot and the eastern bettong.

One of the most damaging invasive species in the Midlands is the feral cat, which is very good at hunting and surviving in the wild. The feral cat’s acute senses and coordination allow it to prey on many native mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and insects. These alien carnivores are responsible for biodiversity loss in the Midlands and are ranked by the Australian Government as the greatest threat to Australia’s mammals. Cats need a large amount of fresh meat to survive and prey on small mammals.

Tasmania’s population of fallow deer had increased to over 30,000 and scientific predictions estimated the population could be more than one million by 2050. Fallow deer, protected in Tasmania for recreational hunting, damage the native vegetation. They destroy young plantings making it necessary to cage all restoration plantings, increasing the cost.

Climate change presents a further serious challenge to these marsupials. If these crucial links in the landscape continue to disappear the region will lose both its beauty and its productivity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the original owners, the Palawa people and the use and crossing of the Midlands where we meet with our partners to share, learn and raise awareness about the land:

Paredarerme nation people, Laremairremener and Poredareme tribes, Luggermairrerpairrer tribe and the Tyrrernotepanner tribe